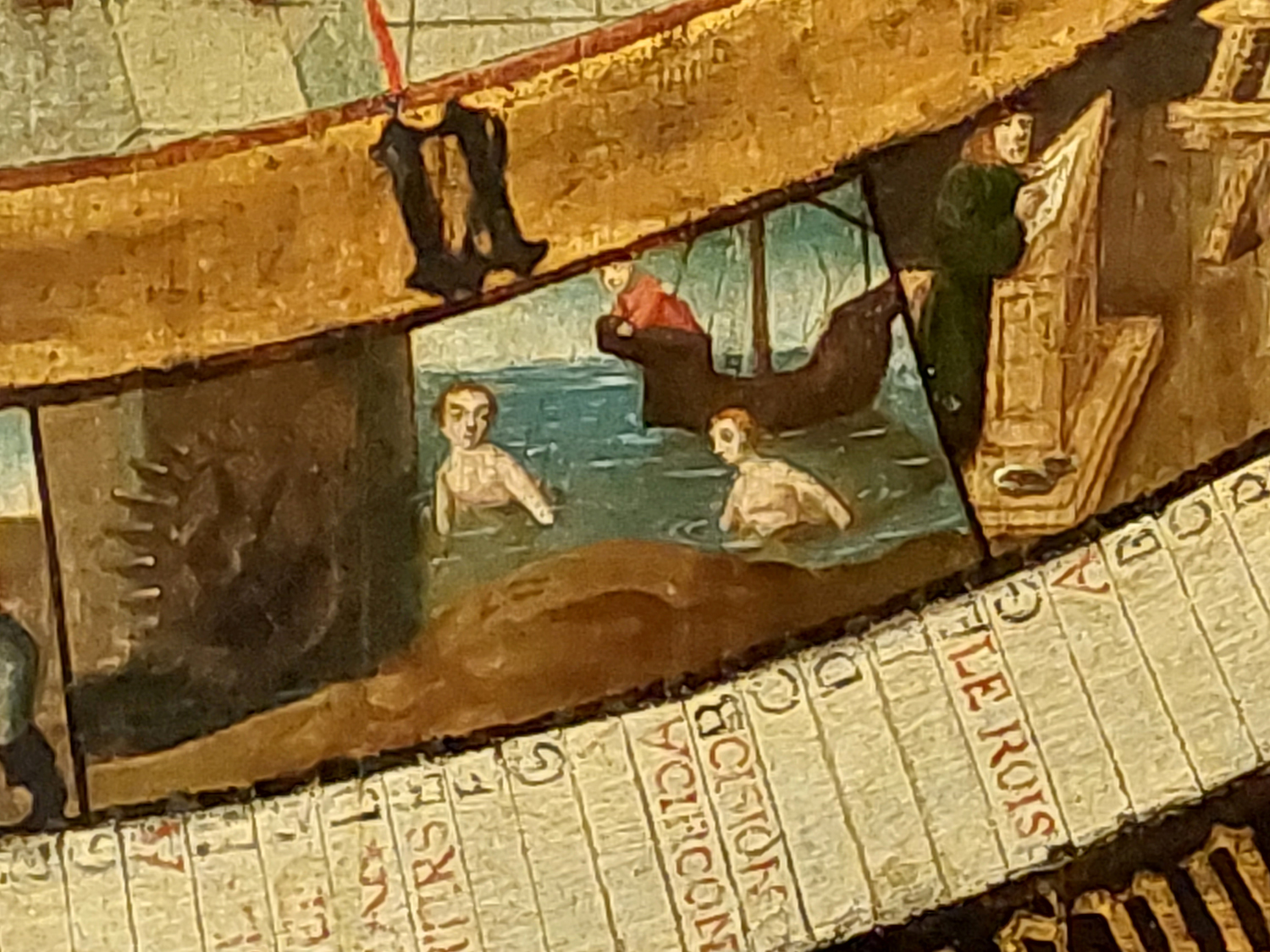

Cykl życia na zegarowo-kalendarzowym panelu autorstwa anonimowego mistrza z Brabancji, ok. 1500 r. Wystawa “Between Paradise and Hell: The Enigmatic World of Hieronymus Bosch”, Muzeum Sztuk Pięknych (Szépművészeti Múzeum). Budapeszt 2022

„Dwa lata wcześniej, na stronicach pewnej encyklopedii-plagiatu, odkryłem zwięzły opis fikcyjnego kraju; obecnie przypadek dostarczał mi czegoś bardziej jeszcze cennego i trudnego. Miałem teraz w ręku obszerny i metodyczny fragment całkowitej historii nieznanej planety, z jej budowlami i wojnami, z przerażeniem jej mitologii i zgiełkiem jej języków, z jej cesarzami i morzami, z jej minerałami, z jej ptakami i rybami, z jej algebrą i ogniem, z jej kontrowersjami teologicznymi i metafizycznymi. I wszystko to na piśmie, spoiste, bez widocznej intencji doktrynalnej czy parodystycznej.

‘Jedenasty tom’, o którym mówię, zawierał odsyłacze do tomów następnych i poprzednich. (…) kim byli twórcy Tlönu? Liczba mnoga jest tu nieunikniona; hipoteza jednego wynalazcy — jednego nieskończonego Leibniza, działającego w ciemnościach i skromności — została jednogłośnie odrzucona. Sądzi się, że ten brave new world jest dziełem jakiegoś tajemnego stowarzyszenia astronomów, biologów, inżynierów, metafizyków, poetów, chemików, moralistów, malarzy, geometrów… pod kierunkiem jakiegoś ukrytego geniusza. (…) Początkowo sądzono, że Tlön jest po prostu chaosem, nieodpowiedzialnym popuszczeniem wodzy wyobraźni; teraz jednak wiadomo, że jest to kosmos i że zostały sformułowane, nawet jeśli w sposób prowizoryczny, wewnętrzne prawa, które nim rządzą. Wystarczy przypomnieć, że w pozornych sprzecznościach Jedenastego Tomu dostrzeżono podstawowy dowód, iż inne tomy istnieją: do tego stopnia przestrzegany w nim porządek jest jasny i konsekwentny.

Popularne czasopisma rozpowszechniły, z wybaczalną przesadą, zoologie i topografie Tlönu; sądzę, że jego przezroczyste tygrysy i krwiste wieże nie zasługują, być może, na nieprzerwaną uwagę wszystkich ludzi. Ale poświęcę kilka minut jego koncepcji wszechświata. (…)

Narody tej planety są — w sposób wrodzony — idealistyczne; język ich i jego pochodne — religia, literatura, metafizyka — zakładają z góry idealizm. Świat, dla nich, nie jest zbiorem przedmiotów w przestrzeni; jest heterogeniczną serią niezależnych czynów; jest następczy, czasowy, nie zaś przestrzenny. W domyślnym Ursprache Tlönu, z którego pochodzą języki i dialekty ‘aktualne’, nie istnieją rzeczowniki; istnieją czasowniki bezosobowe, określane jednosylabowymi przyrostkami (lub przedrostkami) o znaczeniu przysłówkowym. Na przykład: nie ma słowa, które odpowiadałoby naszemu słowu księżyc, ale istnieje czasownik, który brzmiałby u nas księżycznić lub księżycować. ‘Wzeszedł księżyc nad rzeką’ mówi się hlör u fang axaxaxas mlö, to znaczy, w kolejności: ‘Ku górze (upward) za wieczniesączyć zaksiężycowało.’ (Xul Solar tłumaczy krótko: ‘Hop, za przebiegać zaksiężyczniło.’ Upward, beyond the onstreaming, it mooned).

W literaturach tej półkuli (jak w trwającym świecie Meinonga) obfitują przedmioty idealne, powołane i niknące w jednej chwili, zależnie od potrzeb poetyckich. Czasami określa te przedmioty zwykła równoczesność. Niektóre składają się z dwóch terminów, jednego o charakterze wzrokowym i jednego o charakterze słuchowym: kolor rodzącego się dnia i odległy krzyk ptaka. Inne z większej ilości terminów: słońce i woda płynąca naprzeciw piersi pływaka, nieokreślony kolor różowy, który widzi się przez zamknięte oczy, uczucie kogoś, kto pozwala nieść się rzece i, jednocześnie, snowi.

Te przedmioty drugiego stopnia mogą łączyć się z innymi; proces ten, dzięki pewnym skrótom, jest praktycznie nieskończony. Istnieją słynne poematy złożone z jednego tylko, ogromnego słowa. Słowo to odpowiada jednemu przedmiotowi, przedmiotowi poetyckiemu stworzonemu przez autora. Z faktu, że nikt nie wierzy w rzeczywistość rzeczowników, wynika w paradoksalny sposób, że ilość tych ostatnich jest nieskończona.

Równie zaskakujące są i same książki. Wszystkie narracyjne posiadają tę samą fabułę, ze wszystkimi wyobrażalnymi podstawieniami. Książki o charakterze filozoficznym posiadają niezmiennie tezę i antytezę, rygorystyczne pro i contra każdej doktryny. Książka, która nie zawiera swej antyksiążki, uważana jest za niekompletną.

Całe wieki idealizmu nie mogły nie wpłynąć na rzeczywistość. Nierzadko spotyka się w najbardziej starożytnych regionach Tlönu podwojenie zgubionych przedmiotów. Dwie osoby szukają ołówka; pierwsza znajduje go i nic nie mówi; druga znajduje drugi ołówek, nie mniej rzeczywisty, ale bardziej odpowiadający jej oczekiwaniom. Te wtórne przedmioty zwą się hrónirami i są, choć posiadają formę, której brak wdzięku, nieco dłuższe. Do niedawna hróniry były przypadkowymi dziełami roztargnienia i zapomnienia. Do ich metodycznej produkcji — wydaje się to niemożliwe, ale tak wynika z Jedenastego Tomu — przystąpiono przed zaledwie stu laty. (…) Masowe poszukiwania dają w rezultacie przedmioty sprzeczne ze sobą; dziś daje się pierwszeństwo pracom indywidualnym i prawie zaimprowizowanym.

Metodyczne wytwarzanie hrónirów (podaje Jedenasty Tom) dostarczyło nieocenionych usług archeologom. Pozwoliło na badanie, a nawet modyfikowanie przeszłości, która stała się nie mniej plastyczna i uległa niż przyszłość.

Rzecz ciekawa: hróniry drugiego i trzeciego stopnia — hróniry powstałe z innego hrónu; hróniry powstałe z hrónu hrónu — wyolbrzymiają aberracje hrónu pierwotnego; hróniry stopnia piątego są prawie ich pozbawione, dziewiątego mylą się z hrónirami drugiego stopnia, jedenastego mają czystość linii nie posiadaną nawet przez oryginał. Proces ten jest periodyczny: hrón dwunastego stopnia zaczyna się już znowu degradować. Dziwniejszy i bardziej czysty od każdego hrónu jest czasami ur: rzecz wyprodukowana przez sugestię, przedmiot wywołany przez nadzieję”.

Jorge Luis Borges Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius (1941), w: Fikcje, przeł. Andrzej Sobol-Jurczykowski (2019)

“Two years earlier, I had discovered in one of the volumes of a certain pirated encyclopedia a brief description of a false country; now fate had set before me something much more precious and painstaking. I now held in my hands a vast and systematic fragment of the entire history of an unknown planet, with its architectures and its playing cards, the horror of its mythologies and the murmur of its tongues, its emperors and its seas, its minerals and its birds and fishes, its algebra and its fire, its theological and metaphysical controversies—all joined, articulated, coherent, and with no visible doctrinal purpose or hint of parody. In the ‘Volume Eleven’ of which I speak, there are allusions to later and earlier volumes.

(…)

Who, singular or plural, invented Tlön? The plural is, I suppose, inevitable, since the hypothesis of a single inventor—some infinite Leibniz working in obscurity and self-effacement — has been unanimously discarded. It is conjectured that this ‘brave new world’ is the work of a secret society of astronomers, biologists, engineers, meta-physicians, poets, chemists, algebraists, moralists, painters, geometers, guided and directed by some shadowy man of genius. (…) At first it was thought that Tlön was a mere chaos, an irresponsible act of imaginative license; today we know that it is a cosmos, and that the innermost laws that govern it have been formulated, however provisionally so. Let it suffice to remind the reader that the apparent contradictions of Volume Eleven are the foundation stone of the proof that the other volumes do in fact exist: the order that has been observed in it is just that lucid, just that fitting.

Popular magazines have trumpeted, with pardonable excess, the zoology and topography of Tlön. In my view, its transparent tigers and towers of blood do not perhaps merit the constant attention of all mankind, but I might be so bold as to beg a few moments to outline its conception of the universe.

(…)

The nations of that planet are, congenitally, idealistic. Their language and those things derived from their language — religion, literature, metaphysics — presuppose idealism. For the people of Tlön, the world is not an amalgam of objects in space; it is a heterogeneous series of independent acts — the world is successive, temporal, but not spatial. There are no nouns in the conjectural Ursprache of Tlön, from which its ‘presentday languages and dialects derive: there are impersonal verbs, modified by monosyllabic suffixes (or prefixes) functioning as adverbs. For example, there is no noun that corresponds to our word ‘moon,’ but there is a verb which in English would be ‘to moonate’ or ‘to enmoon.’ ‘The moon rose above the river’ is ‘hlör ufang axaxaxasmio,’ or, as Xul Solar succinctly translates: Upward, behind the onstreaming it mooned.

(…)

The literature of the northern hemisphere (as in Meinong’s subsisting world) is filled with ideal objects, called forth and dissolved in an instant, as the poetry requires. Sometimes mere simultaneity creates them. There are things composed of two terms, one visual and the other auditory: the color of the rising sun and the distant caw of a bird. There are things composed of many: the sun and water against the swimmer’s breast, the vague shimmering pink one sees when one’s eyes are closed, the sensation of being swept along by a river and also by Morpheus. These objects of the second degree may be combined with others; the process, using certain abbreviations, is virtually infinite. There are famous poems composed of a single enormous word; this word is a ‘poetic object’ created by the poet. The fact that no one believes in the reality expressed by these nouns means, paradoxically, that there is no limit to their number.

(…)

Their books are also different from our own. Their fiction has but a single plot, with every imaginable permutation. Their works of a philosophical nature invariably contain both the thesis and the antithesis, the rigorous pro and contra of every argument. A book that does not contain its counter-book is considered incomplete.

Century upon century of idealism could hardly have failed to influence reality. In the most ancient regions of Tlön one may, not infrequently, observe the duplication of lost objects: Two persons are looking for a pencil; the first person finds it, but says nothing; the second finds a second pencil, no less real, but more in keeping with his expectations. These secondary objects are called hrönir, and they are, though awkwardly so, slightly longer. Until recently, hrönir were the coincidental offspring of distraction and forgetfulness. It is hard to believe that they have been systematically produced for only about a hundred years, but that is what Volume Eleven tells us. (…) The systematic production of hrönir (says Volume Eleven) has been of invaluable aid to archaeologists, making it possible not only to interrogate but even to modify the past, which is now no less plastic, no less malleable than the future. A curious bit of information: hrönir of the second and third remove — hrönir derived from another hrön, and hrönir derived from the hrön of a hrön — exaggerate the aberrations of the first; those of the fifth remove are almost identical; those of the ninth can be confused with those of the second; and those of the eleventh remove exhibit a purity of line that even the originals do not exhibit. The process is periodic: The hrönir of the twelfth remove begin to degenerate. Sometimes stranger and purer than any hrön is the ur — the thing produced by suggestion, the object brought forth by hope.”

Jorge Luis Borges Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius (1941), in Collected Ficciones of Jorge Luis Borges, translated by Andrew Hurley